| Gizomodo | Erin Biba | 4/11/19 |

Bringing an extinct species back to life was once firmly in the realm of science fiction, but as genetic engineering advances rapidly, the prospect of a woolly mammoth again breathing and walking on Earth seems almost within reach. Before fully resurrecting the mammoth, synthetic biologists at the Revive and Restore project are working to resuscitate pieces of ancient genomes with the goal of mixing them with the DNA of living species (Asian elephants—their closest living relatives) in an attempt to create “proxy species”—animals that display the traits of the ancient original.

The end goal, they say, is to populate the tundra region of Siberia known as the “mammoth steppe” with a herd of as-close-to-mammoth-as-possible animals, using them to bring the ecosystem back to its pre-extinction existence. This, naturally, has brought up some ethical dilemmas: Will science take this further and revive the entire woolly mammoth, not just portions of its genome? What is the motivation for doing any of this? And should we be doing it at all?

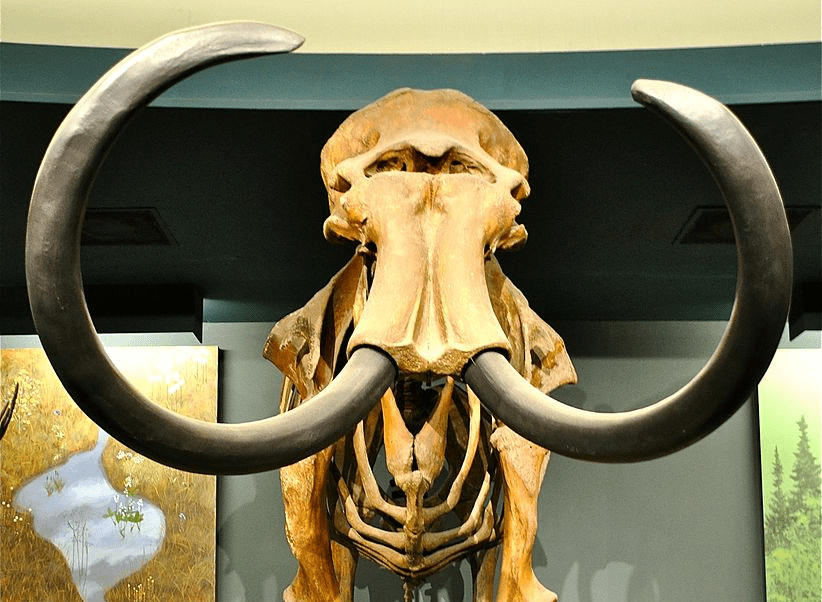

Woolly mammoths lived in Siberia (among other places) during Earth’s last ice age, also known as the Pleistocene Epoch. They were large mammals, essentially big furry elephants with very long tusks, and their population was quite large, which we know from the abundance of fossils that paleontologists have discovered. There are several theories about how they eventually went extinct about 10,000 years ago. Some scientists believe that humans may have hunted them to extinction, and other theories suggest that the end of the ice age and a warming climate actually caused them to die from heat and dehydration.

Reviving a dead species is a controversial idea. While the scientists undertaking the research see it as a way to restore a ruined ecosystem, detractors see the process as unnatural and even an unnecessary show of scientific hubris. Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary microbiologist at UC Santa Cruz and author of the book How To Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-Extinction, told Gizmodo that the act of bringing back an extinct creature could be seen as an extension of humanity’s long history of altering other species for our own benefit. She didn’t see such an experiment as unnatural. Shapiro noted that humans have been domesticating and engineering plants and animals for tens of thousands of years; this is what we’re good at and it’s part of our nature, which means it’s a part of the nature of our planet as well.

However, “there is a strong argument to be made that once something is gone for a long time and the ecosystem has adapted to its absence, it’s hard to imagine everything’s going to return to whatever normal you’re describing,” she said. But, she said, the real and lasting benefit of developing these technologies will be to help species that are currently alive—but increasingly threatened by climate change—remain that way. “We have these big brains that have allowed us to make flint technology and 747s and now CRISPR. We can also use our big brains to think about consequences and think long-term. We have the capacity to plan for the future, so let’s do that.”

[ Read more ]